The Supreme Court could let religious employees wreak havoc in the workplace

Groff v. DeJoy centers around a Christian worker's refusal to work on Sundays, but SCOTUS could open the floodgates for religious accommodation

This newsletter is free, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe to Substack or use my usual Patreon page!

A case being heard by the Supreme Court today could give conservative Christians a powerful new way to use their faith to harm others in the workplace.

As it stands, employers are supposed to “reasonably accommodate” the religious beliefs of their employees as long as it doesn’t create an “undue hardship” on the business. That sounds fair enough. It’s a way to honor Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits religious discrimination in the workplace.

In practice, that might mean being flexible with vacation days so someone can celebrate a religious holiday or giving someone access to an unused room in order to pray during the workday. It doesn’t hurt the company and it’s a minor concession that provides solace for an employee. For a boss to refuse those accommodations, there needs to be a damn good reason. All of that feels sensible enough.

But what happens when a religious demand goes too far?

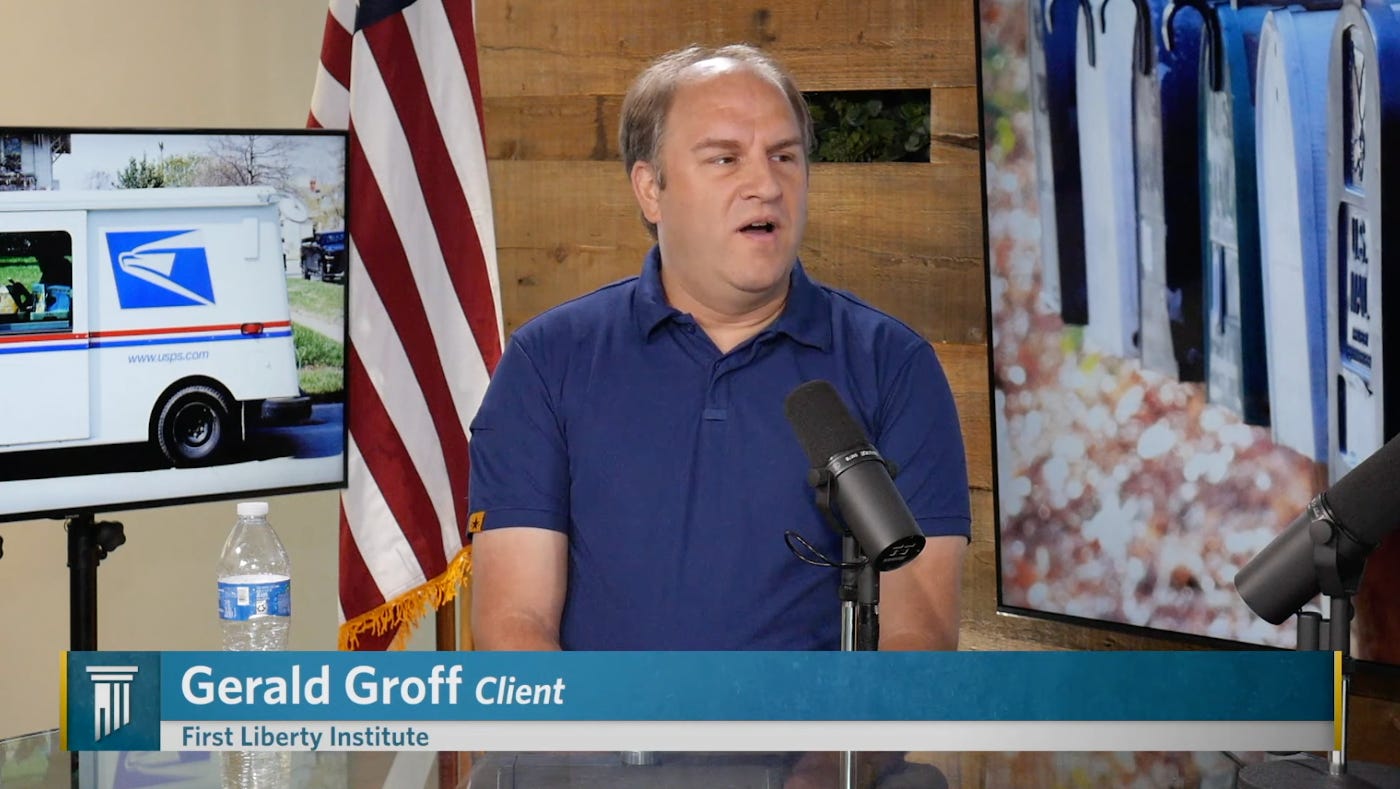

When Gerald Groff began working at a post office in Pennsylvania in 2012, he made what appeared to be a simple request: He didn’t want to work on Sundays because that was the Sabbath. It wasn’t a problem at first because, of course, the mail isn’t delivered on Sundays. But in 2013, the United States Postal Service signed a contract to deliver packages for Amazon on Sundays in some locations. That applied to Groff’s post office starting in 2017.

It wasn’t a problem at first because there were enough employees who, like Groff, worked as Rural Carrier Associates to cover those Sunday shifts. (Career employees do not work on holidays or weekends, which is where the Rural Carrier Associates come into play.) But it became a burden when only a couple of other employees were available to work on Sundays. When a colleague’s injury prevented her from taking Groff’s Sunday shifts, there was no path forward to reasonably accommodate his wishes.

Even beyond that, according to the Department of Justice, Groff’s refusal to work on Sundays “created a ‘tense atmosphere’” in the office and “contributed to morale problems” because other workers had to constantly do his job. One employee transferred out. Another resigned. Another filed a grievance with the union.

Groff eventually missed 24 Sunday shifts that the post office couldn’t cover. He resigned in 2019 after a number of suspensions (with pay). He said he preferred that option over being fired and having that black mark follow him in the future.

This case, then, boils down to the question of whether the post office violated the law by not bending over backwards for Groff’s faith. The post office and the U.S. government say all attempts to accommodate Groff’s religious beliefs were made, and it was only when that became unsustainable that he was told to work on Sundays.

The lower courts agreed with the government: Groff’s requests for special treatment on the basis of his faith were unreasonable, and the post office wasn’t obligated to accommodate him beyond what they already did.

Today, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Groff v. DeJoy. (For a more technical understanding of the laws in question, I urge you to check out Ian Millhiser’s breakdown of this case for Vox.)

The fear is that, because of the way this right-wing Court has rewarded conservative Christians, they could change the law in a way that could lead to a massive loophole just waiting to be exploited by religious workers.

Imagine, for example, a manager who refuses to hire gay people because of his faith, and who demands an accommodation permitting them to discriminate. Or a worker who insists upon preaching their conservative religious views about sexuality or gender roles to their colleagues, even when many of those colleagues feel harassed by this behavior.

If a postal worker is allowed to get out of work on the basis of his faith and put that burden on his colleagues, what’s stopping another employee from demanding the right to proselytize on the job? Or the ability to avoid working next to someone of the opposite sex?

The current standard, established in a 1977 case called Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, said that if there was even a tiny burden on employers, they didn’t need to accommodate a religious request. Even church/state separation groups have long said this is too extreme a standard. But if Groff wins this case, the real concern would be how far this Supreme Court would go (gift article) in revising the status quo:

Rachel Laser, the president of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said the case is “a wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

“Our civil rights laws rightly require religious accommodations for workers, which is especially important for religious minorities whose rights and customs might not be respected in the workplace,” she said. “But religious freedom does not mean we can shift the burden of practicing our faith onto other people. Religious freedom has never been a license to harm others, in employment or any other facet of life.”

Americans United says employers should be able to consider whether accommodating someone’s faith “would impose financial, logistical, health and safety, dignitary, or other burdens on coworkers.”

The Freedom From Religion Foundation, which filed an amicus brief in the case, echoed that argument, saying that “religious employees do not have the legal right to dictate that an employer must impose disruptive conditions on co-workers.”

Incidentally, Groff is represented by First Liberty Institute, the same conservative group that may have helped Matthew Kacsmaryk cover up his alleged authorship of an anti-trans law review article written shortly before becoming a federal judge.

First Liberty wants the justices to change the current law (the “undue hardship” rule) to something that would be much harder to defend in court:

The [First Liberty] brief suggested borrowing a test used in cases under civil rights laws like the Americans With Disabilities Act, one that requires employers to provide an accommodation unless it would impose significant difficulty or expense considering the employer’s resources, the number of people who work for it and the nature of its business.

In other words, who cares if other employees have to cover Groff’s shifts? Because the USPS wouldn’t suffer financially by finding someone else to cover Groff’s shifts, his faith-based request wasn’t really a burden, they say.

As FFRF notes, though, using the Americans With Disabilities Act standard like First Liberty wants still requires employees to show they can perform the job with or without the accommodation, and courts have repeatedly said that requiring other employees to pick up the slack “is not reasonable.” There are hardships on a workplace that can’t be measured in dollars alone:

A sweeping decision from this Court, ruling that burdens on co-workers are never sufficient to establish undue hardship on a business, will disempower courts that have rightly allowed employers to refuse accommodations that would disparage or harass their employees.

For example, FFRF suggests, consider the impact that could occur if a hypothetical male Christian nurse refused to work with a female nurse during an overnight shift because of the “Billy Graham Rule”:

… Given the hospital’s need to provide nursing staff 24 hours a day, the hospital will have administrative difficulty in scheduling the man with only other male nurses or by adding an additional nurse to each of his shifts.

… these examples involve accommodations of employee behaviors that will have immense disruptive effects on the conduct of business, in whole or in large part by their effect on other employees and/or customers. It is not “too speculative”—in fact it is reasonable—for employers to predict that accommodating these behaviors will unduly burden the conduct of business by their effect on customers or other employees in the workplace.

In a separate amicus brief, the Center For Inquiry and American Atheists argue that giving religious conservatives the victory here would put a needless burden on everyone else who has to cover for their colleagues and, in effect, force the government to favor religion over non-religion. That would create a violation of the Establishment Clause:

To permit such favoritism runs contrary to the clear meaning of the First Amendment. It sends a clear message to both nonbelievers and to adherents of religions without Sabbaths that they are inferior under the law and that their families, desires, and activities must take second place to the religious beliefs of their colleagues. It does what this nation was founded to prevent. It creates a privileged caste based on religion.

…

If this Court grants such a privilege to religious claimants, it will not only be abandoning decades of jurisprudence prohibiting the shifting of burdens onto third parties, it will also be abandoning the core of the First Amendment.

At some point, religious requests that create this many problems for everyone else in the workplace cannot and should not be accommodated.

The question now is whether the Supreme Court will give religious conservatives the ability to wreak havoc anywhere they’re hired simply by citing their faith.

This isn't about protecting anyone's rights. This is the attempt to enshrine Christian privilege in law. There isn't much of anything that cannot be justified in the name of religion, and this decision would open the door to a very slippery slope.

I’m suspecting this won’t be the open and shut case some folks expect of the SCROTUS.

On the one hand, this is about Christian privilege and expanding it. Something the SCROTUS is wont to do in the majority of its decisions.

On the other hand, this is also about corporate control. Sure this case is a government entity, but the effects will be felt across the corporate world. Putting burdens on businesses is about the only thing the corrupt in our government will actually stand up to on principle. Their owner donors won’t stand for it, and if Clarence Thomas doesn’t get his luxury vacation he gets mighty grumpy.

So, I am going to bet on SCROTUS making the right decision for all the wrong reasons. Unless they can carve out exceptions for government vs. private corporations, then all bets are off.