The Southern Baptist Convention is still fighting against victims of sexual abuse

A recent amicus brief proves that the SBC still doesn't want abuse survivors to get justice

This newsletter is free, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe to Substack or use my usual Patreon page!

***UPDATE*** (10/30): Bart Barber, the former Southern Baptist Convention president who attempted to put a genial face on the corrupt organization, has admitted he approved the decision to file the amicus brief: “This is my doing. I approved it. I take full responsibility for the SBC’s having joined this brief…”

He said he did it in haste, under a quick deadline, on the advice of lawyers. Which is cold comfort for those who only see the SBC continuing to harm people.

The Southern Baptist Convention has, yet again, found a way to fight against victims of childhood sexual abuse. They’re doing it under the radar, though, which is why survivors and allies are attempting to draw attention to the issue in the hopes that other Southern Baptists (especially their leaders) speak out against the move.

The situation involves a recent law passed in Kentucky to give victims of sexual abuse more time to bring their cases forward while also expanding the types of cases that can be brought.

It was all inspired by Samantha Killary.

From the time she was adopted at the age of two, by Louisville cop Sean Jackman, until she was 18, Killary was sexually assaulted by Jackman. It was only after she secretly recorded him admitting to what he did that he was eventually charged with crimes. In 2018, he was sentenced to 15 years behind bars.

But Killary didn’t just want Jackman to be punished. There were others, she said, who knew what he was doing but chose to keep silent about it. So she sued one of Jackman’s former girlfriends as well as his father. She also sued the police department that employed all of them.

A judge eventually tossed out those other cases, though, because he said the statute of limitations to bring them forward had expired. At the time, victims of sexual abuse only had five years to bring forth their claims… and the assaults against Killary ended back in 2009.

Over the past several years, Kentucky legislators have passed laws giving victims more time to file such lawsuits, following similar moves in other states. Victims in Kentucky now have 10 years to file claims against abuse perpetrators, not just five. And as of 2021, organizations that harbor abusers—whether they’re governmental or religious—are also subject to those lawsuits.

That raises some interesting questions: Can Killary’s lawsuit against everyone else get a second life? More broadly speaking, if alleged abuse occurred before the laws changed, can victims who were previously timed out from filing a lawsuit do so now?

That’s what the Kentucky Supreme Court will have to decide in a case presented to them on Thursday.

One one side, you have victims’ rights groups arguing that giving survivors more time to sue is important for the sake of justice. Many victims don’t realize until it’s too late that they were abused; even those who are aware of what happened may feel hesitant to go after their alleged assailants in court. Allowing older cases of abuse to be tried in court now is vital to fix the mistakes of the past.

On the other side, you have conservative Christians.

There’s some defense for their position, so we might as well acknowledge that. If a victim of abuse wants to sue an alleged perpetrator for actions that took place decades ago, it’s possible the defendant’s memory isn’t as clear and exculpatory evidence isn’t as available as it might have been in the past.

Critics might say, though, that the passage of time shouldn’t whitewash sex crimes and the standards of evidence would still apply. If someone is convicted of sexual abuse, who cares when it occurred? Let the survivors have their day in court. The standards of evidence still apply, after all. It’s not like the courts are suddenly ignoring the burden of proof.

Yet for years now, we’ve seen religious organizations fight laws that extend or eliminate statutes of limitations in these cases. The Catholic Church has routinely done this in states that pass laws favorable to victims. It’s obvious why they’re doing it. When victims are able to sue them, dioceses often have to declare bankruptcy.

You would think Southern Baptists, who have gone through a public reckoning regarding their own sexual abuse problems, would want to avoid publicly siding with abusers.

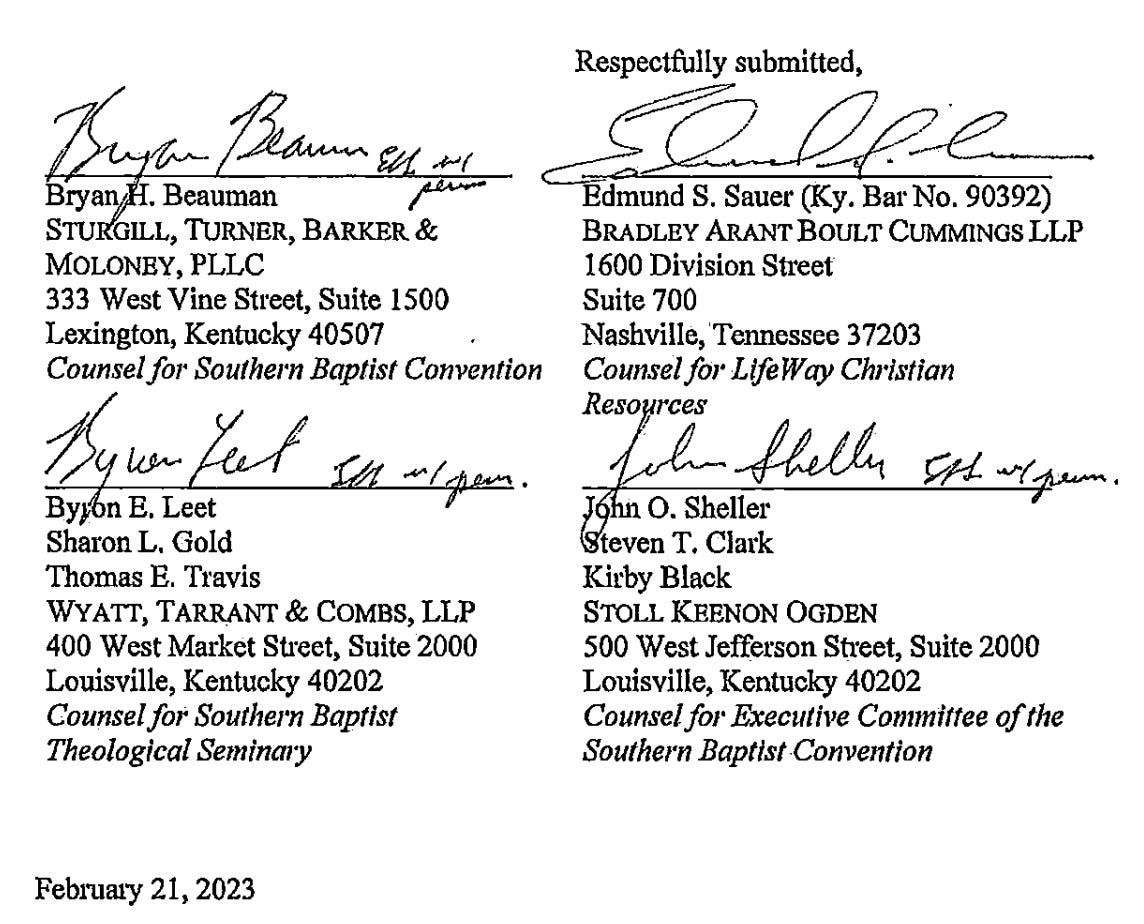

But even though the Southern Baptist Convention and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary had nothing to do with Killary’s case, their lawyers still filed an amicus brief with the court urging the judges to toss out Killary’s lawsuit, in part because they might suffer if the Court rules the other way.

While the brief was filed in April, it appears no one picked up on it until the Courier-Journal reported on it earlier this week.

In their brief they say they “of course do not dispute the laudable policy reasons for providing relief for victims of childhood sexual abuse.”

But “not even the most sacrosanct policy can trump the due process concerns presented in this and similar cases involving the attempted retroactive application of expired claims,” they say.

The brief says the seminary and convention, a fellowship of 47,000 churches, are themselves on the hook for claims dating to 2003 that they knew about abuse and violated their duties in responding to it.

In other words, a lot of people are suing us for abuse that occurred decades ago, and we’d like to wipe our hands clean of those pesky problems, so can you pretty please make it harder for victims to come after us?!

The fact that the SBC chose to inject itself into this particular case has infuriated people within Baptist circles who have been pushing for change, both internally and externally.

For example, members of the SBC Sexual Abuse Task Force, which was formed in 2022 to implement abuse reforms, expressed “deep grief” that such a brief was filed at all:

This brief and the policy arguments made in it, were made without our knowledge and without our approval. Moreover, they do not represent our values and positions.

It has long been recognized that access to the justice system is a fundamental part of identifying and stopping abusers, as well as creating lasting, effective reform to protect the next generation. By taking this stand against access to the justice system, the leaders who approved this position have joined with the Catholic Church, powerful insurance companies, Michigan State University, and many others who have sought to close the halls of our courts to survivors of abuse. And it was a choice to stand against every survivor in Kentucky.

Oof. You know the Catholic Church’s reputation is in the gutter when criticism of the Southern Baptist Convention includes the phrase, “By taking this stand against access to the justice system, the leaders who approved this position have joined with the Catholic Church…”

They noted that opening up older cases may create “valid factual questions” about what happened, but opposing Killary, they added, “is a deliberate effort to ensure those questions are never asked.”

Another powerful statement came from Megan Lively, Jules Woodson and Tiffany Thigpen, three women who have been courageous and outspoken about the need to reform the SBC. They said they were “sickened and saddened to be burned yet again by the actions of the SBC against survivors.”

… The SBC proactively chose to side against a survivor and with an abuser and the institution that enabled his abuse, arguing that Samantha should not even be given access to the court system—that statute of limitations reform does not extend to institutions. These are the same arguments made repeatedly by organizations rife with the cover-up of sexual abuse, including the Catholic Church.

In addition to urging allies to stand with survivors, the women are asking “SBC member bodies to denounce the activities, enormous costs, and pain of the double-edged sword being shown against survivors and reform in the SBC.” They also want transparency when it comes to how much money the SBC is spending to fight victims of sexual abuse compared to the money they’ve invested in supposed reform efforts.

Bob Smietana of Religion News Service puts this all in context:

For decades, leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention have sought to protect the nation’s largest Protestant denomination from any liability for sexual misconduct at local churches.

That legal strategy led SBC leaders to downplay the scope of abuse in the denomination, to treat abuse survivors as their enemies and to stonewall attempts to address abuse on a national level for years. While the denomination’s annual meetings have apologized for the past behavior of leaders, the SBC has struggled to move forward with reforms while dealing with its legal challenges.

There’s no way to move forward with abuse reform when the SBC is still dead set on making sure victims of abuse aren’t able to seek justice.

So who approved getting involved in this case?! Who in SBC leadership thought this amicus brief—which they absolutely did not have to file—was worthy of their time and energy? If the end result is that more victims can get justice against their assailants and the institutions that gave them cover, why does the SBC feel the need to get in the way rather than face any potential-but-well-deserved consequences?

We know the answer. (Well, most of us do.)

It seems like the SBC knows what the answer should be, too, because they don’t seem eager to answer questions about this brief at all. Smietana did, however, obtain this statement out of them:

In a statement Friday (Oct. 27), the Executive Committee’s officers confirmed that no trustees approved the amicus brief. Instead, according to the statement, the committee joined the brief on the advice of their attorneys. The statement does not address who approved joining the brief. At the time the brief was filed, the Executive Committee was led by former interim president Willie McLaurin, who resigned in August after admitting he’d faked his resume.

“The filing of this amicus brief, and the response to it, have prompted the current SBC Executive Committee trustees to reevaluate how legal filings will be approved and considered in the future. We will be diligent in addressing those concerns,” the statement read.

They didn’t approve it… but their attorneys told them it was a good idea… but no one wants to take responsibility for it… and the guy who might have green-lit the brief resigned because he was a liar. Just a perfect encapsulation of religion: Bad ideas mixed with a complete lack of leadership.

The idea that attorneys just told them to do it is absurd, too. Look at how many lawyers worked on this brief! 8 of them! You know they communicated about this! How could this many people representing this many groups work on something of this magnitude without any awareness from the top brass at the SBC?

The full statement from the SBC Executive Committee isn’t much better. It says the brief “does not take a position on the underlying litigation, and it is not a lobbying effort to restrict statutes of limitation. Rather it urges the court to apply the current Kentucky statute as it was drafted and intended.” But let’s be honest: Urging the court to interpret a law in a way that benefits abusers over victims is a choice.

Southern Seminary president Al Mohler didn’t do any better with his statement, deferring all questions to legal counsel (which would be fine!), but adding that, “in questions of law, significant constitutional and legal questions arise and require arguments to be made before courts,” which is the kind of bland statement you expect to see on page 1 of a law school textbook. It’s not what anyone with real human emotions would ever say if victims were truly at the forefront of their mind.

The question now is whether people who still consider themselves Southern Baptists are willing to admit this organization isn’t worth their time and money and finally leave for good.

All bureaucracies tend to be self-perpetuating. None more so than religious institutions. While religion and morality are not mutually exclusive, they are very far from the same thing. By trying to fight against the victims of sexual abuse at the hands of their institution, the Southern Baptists demonstrate the disconnect between religion and morality about as well as it can be. They are attempting to circle the wagons and protect their church, while offering up thoughts and prayers for their victims. And they wonder why fewer, and fewer people are showing up on Sunday mornings.

In other news, water is still wet, bears shit in the woods, and Francisco Franco is still dead.