Ten Commandments posters must go up in schools before Louisiana families can sue, says federal court

The Fifth Circuit admitted the law may be unconstitutional, but they're forcing students to endure religious displays before challenging them

This newsletter is free and goes out to over 23,000 subscribers, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe or use my usual Patreon page!

In a decision that seems pointless as much as it is frustrating, an appellate court ruled that the Ten Commandments can be posted in Louisiana public schools and that legal challenges against it cannot be filed until after that happens.

A previous lawsuit to block Louisiana’s Ten Commandments law had been successful at the district court level and the appellate court level—the judges even said the law was “plainly unconstitutional”—but the full Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals asked to reconsider the case and they’ve now decided 12-6 to overturn their colleagues’ earlier decision. (You can read the longer history of this case here.)

When a subset of those judges ruled in the Plaintiffs’ favor last year, the judges said they didn’t need to wait for the Ten Commandments to be posted because the law already made clear what those posters would have to say. Why force children to be subject to religious proselytization when you can prevent it in advance? In fact, the District Court judge said letting the law go into effect (so the Plaintiffs would encounter the displays) would be a “considerable hardship” upon those families. There was no need to wait, he wrote, when the law was this blatantly illegal.

That’s apparently not how the full Fifth Circuit saw it.

They wrote in their 46-page decision that the families involved needed to wait to see the posters before they could sue “because we do not yet know—and cannot yet know—how the text will be used.” (In legal terms, they said the case was not “ripe” yet.)

Asking us to declare—here and now, and in the abstract—that every possible H.B. 71 display would violate the Establishment Clause would require precisely what Texas forbids: the substitution of speculation for adjudication. It would oblige us to hypothesize an open-ended range of possible classroom displays and then assess each under a context-sensitive standard that depends on facts not yet developed and, indeed, not yet knowable. That exercise exceeds the judicial function. It is not judging; it is guessing. And because it rests on conjecture rather than a concrete factual record, it does not cure the ripeness defect—it compounds it.

…

We do not know, for example, how prominently the displays will appear, what other materials might accompany them, or how—if at all— teachers will reference them during instruction. More fundamentally, we do not even know the full content of the displays themselves. Although the statute requires inclusion of the Commandments and a context statement, it expressly permits additional content—such as “the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence, and the Northwest Ordinance”—to appear alongside them.

There’s a lot of B.S. packed into those paragraphs.

We know that because their own members said as much earlier. In the Fifth Circuit panel decision from June, the judges said they knew what the posters would look like because the specs were listed in the bill. They knew the size and the wording, adding “The text of H.B. 71 provides sufficient information for a fact-intensive and context-specific analysis.”

It’s also worth mentioning those those secular texts, like the Mayflower Compact and the Declaration of Independence, are not required to go up alongside the Christian posters. They’re optional. The Christian message, on the other hand, is mandatory. That was the problem.

One of those previous judges predictably dissented with the new ruling, explaining that nothing in his earlier reasoning had changed:

Bound by Stone v. Graham and its progeny, and mindful that we are not the Supreme Court, I conclude that permanently posting the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom, without curricular incorporation and with compulsory attendance, violates the Establishment Clause. Our court avoids confronting that conclusion only through procedural artifice. I dissent.

The reason several judges said they didn’t need to wait was because Louisiana officials had already offered up examples of what the Ten Commandments posters could theoretically look like and they were all legal disasters. Attorney General Liz Murrill even held a press conference in which she displayed multiple examples of those posters that she said would be welcome in public schools and couldn’t possibly offend anyone.

How pathetic was that defense?

Consider this sample poster that included a picture of the late Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and a quotation in which she referred to the Commandments as one of the world’s “four great documents.”

Murrill said that the line came from something RBG “wrote in [her book] My Own Words.”

Except RBG didn’t write those words at any point in her legal career. She wrote them in 8th grade. She simply reprinted that old essay in the book:

Murrill was literally quoting RBG’s opinion when she was barely a teenager because quoting anything RBG ever wrote as a sitting Supreme Court justice would undoubtedly go against Louisiana’s theocratic law.

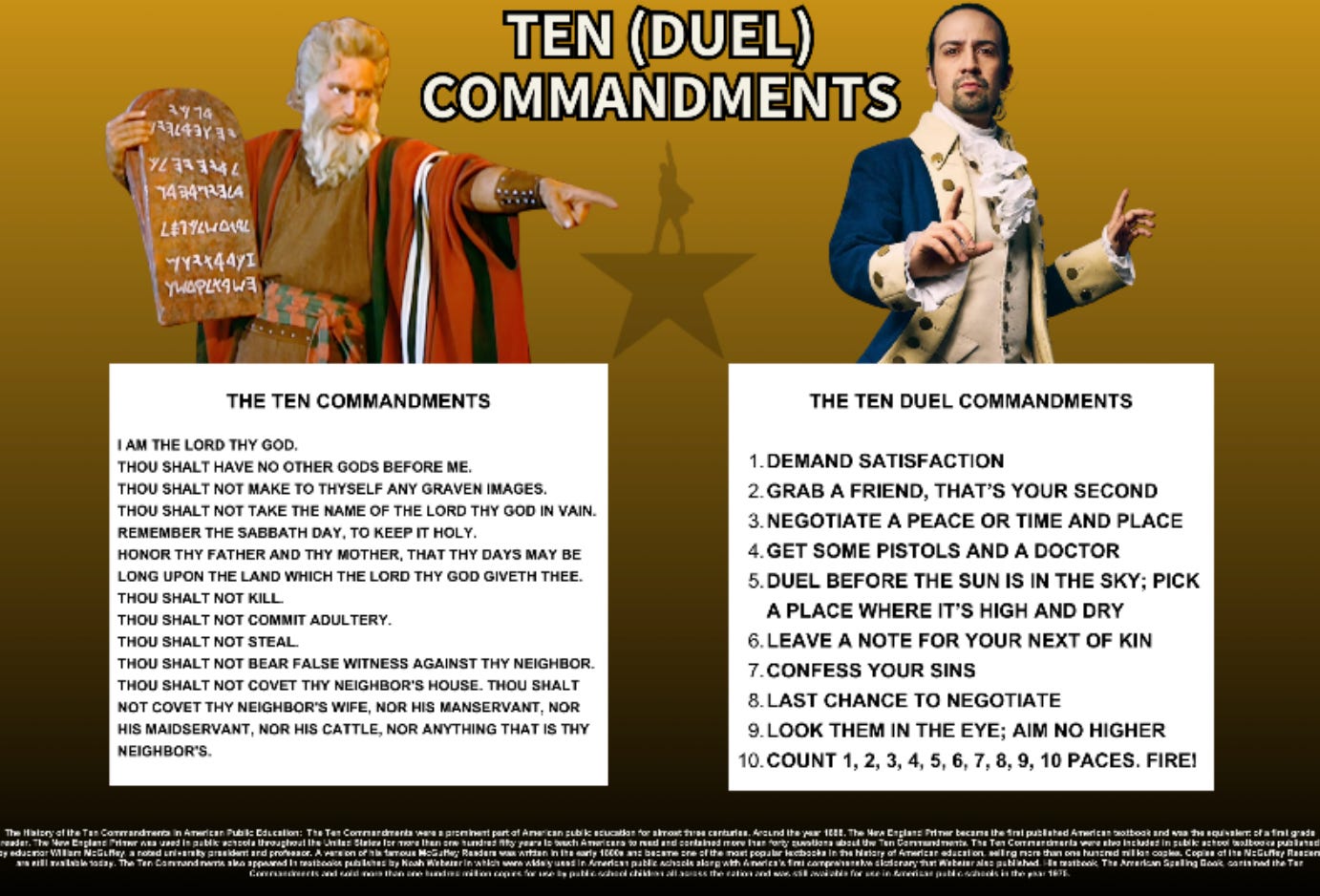

Another sample poster compared the Ten Commandments to the Ten Duel Commandments from Hamilton:

How that made anything better was anyone’s guess. Louisiana officials were trying to distract people from their actual goal of shoving Christianity in everyone’s faces.

To put it another way, there was no way to implement the Ten Commandments law without creating even more legal problems.

But now, apparently, we have to wait for those posters to go up before another lawsuit can be filed because only then will the judges be able to figure out if these posters are truly about promoting one specific religion.

The legal groups that represented the Plaintiffs expressed their disappointment with the decision:

Represented by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, the ACLU, ACLU of Louisiana, and Americans United for Separation of Church and State, with Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP serving as pro bono counsel, the plaintiffs in Roake v. Brumley are a multifaith group of nine Louisiana families with children in public schools. The organizations representing the plaintiffs issued the following statement in response to the decision:

“Today’s ruling is extremely disappointing and would, if left in place, will unnecessarily force Louisiana’s public school families into a game of constitutional whack-a-mole in every school district where they must challenge each individual school district’s displays. Longstanding judicial precedent makes clear that our clients need not submit to the very harms they are seeking to prevent before taking legal action to protect their rights. But this fight isn’t over. We will continue fighting for the religious freedom of Louisiana’s families.”…

The plaintiffs’ counsel is exploring all legal pathways forward to continue the fight against this unconstitutional law.

They’re not disappointed because they lost. They’re disappointed because the conservative court is making their clients jump over pointless hurdles in order to say all of the same things as before. They may very well win this case—but they’ll now have to wait several more months to get the response they could have gotten right now.

They also point out, however, that this ruling has nothing to do with a separate challenge against Texas’ Ten Commandments law. The same full Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals heard that case about a month ago.

Incidentally, one of the judges, archconservative and Trump appointee James C. Ho, wrote that he would simply allow the law to remain in place because he thinks promoting Christianity in schools is perfectly legal. He also called on the Supreme Court to overturn Stone v. Graham, a 1980 decision that said putting the Ten Commandments on classroom walls was unconstitutional because it lacked a nonreligious, legislative purpose.

Once Stone is removed, this case should be easy to dismiss. Plaintiffs present no historical evidence that remotely suggests that our Founders would have regarded a passive display of the Ten Commandments as an impermissible “establishment of religion.”

Ho went on to say that the Ten Commandments was just part of American history because it was used in the New England Primer, McGuffey’s Readers and Noah Webster’s American Spelling Book. But all three books were literally mentioned in the earlier decision by U.S. District Judge John deGravelles. He explained that the New England Primer was used almost exclusively in religious schools long before the rise of public education. And while some McGuffey’s Readers included a story about the Ten Commandments, others didn’t. And there are all kinds of reasons all of these texts went out of style over the past century.

When lawyers on the side of church/state separation argued against the law in Louisiana, they said “there is no evidence of a longstanding, let alone unbroken, historical acceptance and practice of widespread, permanent displays of the Ten Commandments in public schools.”

And yet Ho fell for the lie without giving it a second thought.

Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry didn’t mind at all. He celebrated the new ruling, saying “Common sense is making a comeback!”

Common sense would be allowing teachers to do their jobs instead of becoming state-sponsored preachers.

Murrill joined in with her own absurd statement saying “Don’t kill or steal shouldn’t be controversial”:

If the two commandments about killing and stealing are the only ones she wanted up in classrooms, we’d be having a different conversation. But she’s lying and purposely misleading people about what the real controversy is. Murrill also claims she released legal posters but those are the problematic ones I already described earlier.

Their statements are ridiculous because we already know how this will play out:

A school district will put up the Ten Commandments posters in classrooms.

Families will sue.

The lower court judge will inevitably side with them, saying the posters are illegal.

Louisiana officials will appeal.

The Fifth Circuit will have to weigh in once again… and we’ll be right back to where we started. Only this time they’ll have to rule on the merits.

Which is a long way of saying the Fifth Circuit is simply delaying the inevitable. That’s probably the point. They’re buying time for the Christian posters to go up, perhaps hoping the other side will just give up.

What makes this ruling so annoying is that the Fifth Circuit isn’t grappling with a difficult constitutional question; it’s avoiding one. The judges know exactly what Louisiana intends to do because Louisiana told them. There’s nothing speculative about forcing a religious document onto classroom walls. By declaring the case not “ripe,” the Fifth Circuit has insulated a plainly unconstitutional law long enough for it to cause real harm. Families who already know their rights are being violated must now wait until their children are subjected to state-sponsored religious messaging before they can seek relief. That’s not how constitutional protections are supposed to work. The First Amendment exists to prevent violations, not to require victims to endure them first so courts can acknowledge the obvious.

The Fifth Circuit had every opportunity to stop this abuse of Republican power before it began. Instead, it chose to step aside because some judges didn’t want to enforce the Constitution. This is all nothing more than a stalling technique.

Pointless all the way!

As I said in a previous post: Xtianity is a cult that needs to indoctrinate children because it cannot rest upon any merits it has (it has none). The cult needs unformed, submissive minds to keep a ready supply of sexual victims and handmaids at hand.