Federal judge strikes down Louisiana law forcing Ten Commandments displays in classrooms

Shoving Christianity in kids' faces through their public schools is still, for now, illegal

This newsletter is free, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe to Substack or use my usual Patreon page!

It turns out shoving the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms is still—thankfully and at least temporarily—illegal. Today, U.S. District Judge John deGravelles, who was nominated to his seat by President Barack Obama, ruled that a Louisiana law endorsing Christianity in public schools is “unconstitutional on its face.” That decision will undoubtedly be appealed, but for now, it’s a huge victory for church/state separation.

How the hell did we get here, and what did the judge actually say?

What the Ten Commandments law said

HB 71, sponsored by Republican State Rep. Dodie Horton, initially said that the “Ten Commandments shall be displayed on a poster or framed document that is at least eleven inches by fourteen inches. The text of the Ten Commandments shall be the central focus of the poster or framed document and shall be printed in a large, easily readable font.”

The Ten Commandments bill sailed through the State House on a 82-19 vote and eventually, after some modifications, made it through the State Senate 30-8. While some Democrats voted for the bill, the no votes all came from their side.

It’s no wonder those Democrats were against it. The bill even specified the text that each Ten Commandments poster had to display:

The Ten Commandments

I AM the LORD thy God.

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven images.

Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.

Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Honor thy father and thy mother, that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

Thou shalt not kill.

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Thou shalt not steal.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's house.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor's.

(If you counted more than 10 commandments on that list… well, congratulations. You’re not alone.)

The House bill said schools had to pay for the posters themselves (through their own funds or through donated funds), but that they could also accept donated displays. Nowhere in the bill did it say what the penalty would be for schools that refused to participate in this Christian charade.

This was obviously a blatant attempt to inject Christianity into public schools. To quote a federal judge who once declared illegal a Ten Commandments monument outside a Pennsylvania public school, “There is no context plausibly suggesting that this plainly religious message has any broader, secular meaning.” From the line “I AM the LORD thy God,” this was an endorsement of a very specific brand of Christianity, and the government had no business telling students what religious rules they need to follow.

Horton’s bill was so egregiously illegal that a virtually identical version failed to pass in freaking Oklahoma earlier this year

Why the Ten Commandments are bad policy

It’s genuinely bizarre that the same people who don’t want high schoolers learning about sex, systemic racism, or LGBTQ people have very specific things they want kindergartners to know about adultery and their neighbor’s maidservants.

As I’ve said before, this was always a meaningless gesture. No potential school shooter has ever plotted out a path of destruction only to reconsider after realizing the Ten Commandments say “Thou shalt NOT kill.” If students need a sign to remind them not to murder others, they have bigger issues. It would be great if they could see a mental health professional, but Louisiana lawmakers are more interested in getting Christian chaplains in schools than hiring actual experts.

It goes without saying that several of the Commandments are flat-out useless when it comes to instilling morality since they forbid believing in false gods, making “graven images,” taking God’s name in vain, and not keeping the Sabbath day holy.

What was the educational benefit of telling children they couldn’t have other gods before the One True Christian God™? Or that they couldn’t make false idols? Or they couldn’t take God’s name in vain? Or that they had to rest on Sunday? Or that they couldn’t have sex with people they’re not married to? Or that they couldn’t want what their neighbors have? Beats me.

Did kindergartners really need to be told not to commit adultery? (If that line were in a library book, you know these same Christians would try to get it banned.)

Even beyond that, public school teachers weren’t clamoring for the government to give them this distraction.

The Louisiana Senate tried fixing the bill but they didn’t do enough

The State Senate apparently knew Horton’s bill wouldn’t hold up against a legal challenge. That’s why the bill they passed included a set of important changes that they felt might blunt the problems in the original version.

For example, in their version of the bill, the Ten Commandments posters had to include a disclaimer of sorts—one that offered its supposed historical context, citing the Decalogue’s use in education long before our country was as religiously diverse as it is today.

That fine print, however, wouldn’t negate the fact that this was still a religious imposition upon schools.

Another change? The bill would allow schools to put up copies of the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence, and the Northwest Ordinance alongside the Ten Commandments. That would suggest the Commandments are one of many ancient documents that inspired our legal system… but schools wouldn’t be required to put those other documents up. If the bill said the Christian list was mandatory but the secular texts were optional, it would still be an illegal promotion of religion. It didn’t help that those three other documents all affirmed the importance of faith in one way or another.

Finally, the Senate version of the bill explicitly said no public funds could be used for the displays. Only donations of posters (or donations of cash to purchase posters) would be accepted.

The bottom line was that schools would still be forced to put up the Ten Commandments posters. Which meant the Senate’s changes wouldn’t be enough to avoid lawsuits. Without those changes, the Louisiana bill would have been dead on arrival, but even with those changes, it wasn’t much better.

As one Democrat said at the time, the Christian Nationalist bill was “unconstitutional, exclusionary, and dangerous. By endorsing a state-sanctioned religion, they undermine the foundational principle of religious freedom upon which the United States was built upon.”

It didn’t take long before Gov. Jeff Landry signed that bill into law. He even said in a speech that he couldn’t "wait to be sued."

The lawsuit was filed immediately

His wish was quickly granted. A coalition of religion and non-religious plaintiffs backed by several groups that fight for church/state separation sued Louisiana officials who were on the State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education along with Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley. They also sued the individual school districts that the plaintiffs and their children belonged to. (Landry himself was not a defendant in the lawsuit.)

The ACLU, the ACLU of Louisiana, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, and the Freedom from Religion Foundation—along with the New York City law firm Simpson, Thatcher & Bartlett—said that HB 71 “substantially interferes with and burdens” their clients’ First Amendment freedoms. By mandating the KJV Ten Commandments be displayed in every classroom, the state was effectively telling kids which religion counted—and which ones didn’t. The practical consequence of that message was to teach kids from non-KJV families that they were second-class citizens.

Right from the beginning, the lawsuit made clear there was “no longstanding tradition” of displaying the Ten Commandments in public spaces and no legal precedent to back up that notion. Why did that matter? The Supreme Court has destroyed the Lemon Test, which offered a method to determine if a law violated church/state separation. Instead, when it comes to religious elements on public property, they now say what matters is tradition. If a Christian cross, for example, has been up on city property for decades and decades without complaint, then that’s justification enough for it to be allowed to remain there. This lawsuit, however, said that argument couldn’t work here because that tradition didn’t exist.

The lawsuit also cited some of the Republicans who sponsored the bill, pointing out how they made clear the goal was shoving their personal religion in kids’ faces:

The law’s primary sponsor and author, Representative Dodie Horton, proclaimed during debate over the bill that it “seeks to have a display of God’s law in the classroom for children to see what He says is right and what He says is wrong.”

…

… Representative Roger Wilder, another co-author and co-sponsor of H.B. 71, expressed his support for the law by claiming that those who oppose it are waging an “attack on Christianity” and suggesting that it would provide a religious counterbalance to students’ secular education: “My wife is a Christian and if she was a teacher she would be asked to teach evolution which is in complete contradiction with the theory of creation that we believe out of the Bible. . . . I am a parent and am asking for this [bill].”

What about the bill itself? Even that inadvertently gave away the game. For example, while the bill said the Decalogue had to be displayed on a poster that’s at least 11” by 14” and while the text had to be large and legible, there were no such rules for the disclaimers that also had to be displayed next to those posters.

Nor were there size or legibility requirements for the optional additional documents, like the Mayflower Compact and the Declaration of Independence, that schools could place next to the Ten Commandments.

What about the argument that the Founding Fathers wanted this?

The bill said President James Madison once stated "(w)e have staked the whole future of our new nation . . . upon the capacity of each of ourselves to govern ourselves according to the moral principles of the Ten Commandments.” But the lawsuit pointed out how that quotation was bullshit: “Madison never said this in any of his public or private writings or in any of his speeches.” The Guardian reported that the fake line “appears to have been drawn from a conspiracy theory popularized by the late rightwing talk show host Rush Limbaugh.” Christian pseudo-historian David Barton has also spread the lie.

The lawsuit noted that many citizens actively reject parts of the Ten Commandments, that the specific KJV text of the law isn’t even used by many Christians, and even the numbering of the Commandments is different based on which part of the Bible you’re citing: “Among those who may believe in some version of the Ten Commandments, the particular text that they follow can differ by religious denomination or tradition. For instance, Catholics, Jews, and many Protestants differ in the way that they number, organize, and translate the commandments from Hebrew to English.”

Then there was the obvious coercion factor. Students as young as kindergarten would be “pressured into religious observance, veneration, and adoption of this religious scripture.” Those who rejected the list may feel publicly ostracized. And the parents who didn’t subscribe to KJV or Christianity in general shouldn’t have to deal with their kids’ public schools usurping their own roles in directing their education.

The lawsuit said the state was violating the First Amendment’s Establishment and Free Exercise clauses. They wanted the judge to strike it down entirely, then make the Louisiana officials send a notice to all schools in the state that the law no longer applied, along with all attorneys’ fees covered by the defendants.

Louisiana tried defending the secularity of the law

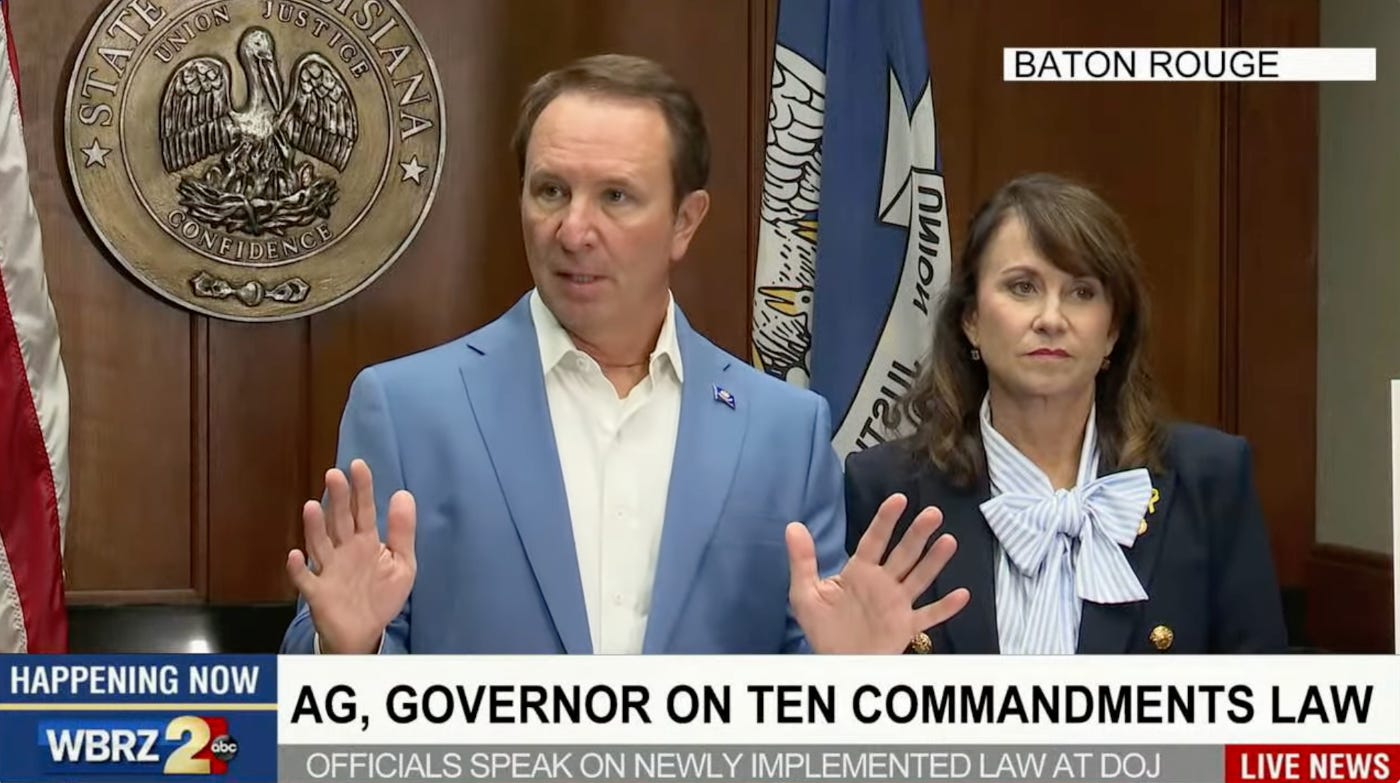

In August, Attorney General Liz Murrill, along with Gov. Landry, held a press conference to announce that the state was asking the federal judge to toss out the lawsuit because the plaintiffs had no standing. After all, they explained, the law didn’t go into effect until January 1, and none of the posters had even gone up in classrooms yet, so what the hell was everyone complaining about?

Landry claimed the bill had bipartisan support (as if the First Amendment was subject to popular vote when it came to endorsing religion) and that parents who opposed the posters could simply tell their child “not to look at it.” It was the sort of response you only ever hear from Christians who expect their religion to be treated as the default. It’s everyone else’s job to ignore Christian propaganda, not the government’s responsibility to avoid promoting a favored religion.

Murrill’s commentary was even worse. She displayed multiple examples of posters that she said would be welcome in public schools and couldn’t possibly offend anyone. (The same images also appeared in the 60-page brief they filed with the judge.)

Just to give you one example of how pathetic her defense was, consider this sample poster that included a picture of the late Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and a quotation from her referring to the Commandments as one of the world’s “four great documents.”

Murrill said in the legal filing that the line came from something RBG “wrote in [her book] My Own Words.”

Except RBG didn’t write those words at any point in her legal career. She wrote them in 8th grade. She had just reprinted that old essay in the book:

Murrill was literally quoting RBG’s opinion when she was barely a teenager because quoting anything RBG ever wrote as a sitting Supreme Court justice would undoubtedly go against Louisiana’s theocratic law.

The question was whether any of this would matter. Judge deGravelles already said no schools could put up the Commandments until at least November 15, giving him time to consider the merits of the lawsuit.

And now he’s made his decision.

The judge didn’t buy the state’s arguments at all

The 177-page ruling leaves nothing unsaid.

DeGravelles argues that the facts of the case violate a Supreme Court ruling from nearly five decades ago, Stone v. Graham, that declared a virtually identical law in Kentucky unconstitutional. Ominously, he writes, “this District Court remains bound to follow Stone until the Supreme Court overrules it.”

Even if the law didn’t invoke Stone, though, deGravelles says the law would still be illegal in light of what the current Supreme Court ruled in the Bremerton case (involving the showboating Christian football coach who wanted to pray at midfield after games) because there’s no tradition of posting the Commandments in classrooms.

In sum, the historical evidence showed that the instances of using the Ten Commandments in public schools were too “scattered” to amount to “convincing evidence that it was common” at the time of the Founding or incorporation of the First Amendment to utilize the Decalogue in public-school education... That is, the evidence demonstrates that the practice at issue does not fit within and is otherwise not consistent with a broader historical tradition during those time periods.

What a way to dismiss something that is treated as gospel by a bunch of gullible white evangelicals. The idea that Christianity was baked into the public schools during our nation’s earliest years was never true, but conservatives keep pretending it was, and this judge just swatted it away in a few sentences.

Finally, he said, making kids look at the Christian displays at school is absolutely coercive.

Each of the Plaintiffs’ minor children will be forced “in every practical sense,” through Louisiana’s required attendance policy, to be a “captive audience” and to participate in a religious exercise: reading and considering a specific version of the Ten Commandments, one posted in every single classroom, for the entire school year, regardless of the age of the student or subject matter of the course.

What about the argument that Murrill’s sample posters showed that the Ten Commandments could be displayed in a secular context without shoving Christianity in kids’ faces?

The judge didn’t fall for it:

AG Defendants treat this as a kill shot. They maintain that they can comply with the Establishment Clause by surrounding the Ten Commandments with nonreligious matter no matter how outlandish that material might be. That is to say, AG Defendants believe they can constantly change their iterations, leaving potential challengers like Menelaus trying to seize and hold the ever shape-shifting Proteus until Proteus eventually tires and divulges the hero’s way off the island... Or, phrased another way, AG Defendants would have aggrieved parents and children play an endless game of whack-a-mole, constantly having to bring new lawsuits to invalidate any conceivable poster that happens to have the Decalogue on it.

AG Defendants overreach. Critically, they ignore the fact—both in briefing and in many of their Illustrations—that the Act contains certain “minimum requirements” that the Ten Commandments “shall be displayed on a poster or framed document that is at least eleven inches by fourteen inches,” with the Decalogue as “the central focus of the poster or framed document” and “printed in a large, easily readable font.”

In other words, the law is very specific about how the Christian message must be elevated in a way that never applies to the parts around it. So don’t be fooled be the distractions. The law itself endorses Christianity in a way that’s unconstitutional because it’s “overtly religious.”

He adds that the question isn’t whether the Commandments can be displayed in a classroom; it’s “whether, as a matter of law, there is any constitutional way to display the Ten Commandments in accordance with the minimum requirements of the Act.” (Emphasis his.)

The answer?

“In short, the Court finds that there is not.”

As for standing, the judge said that by letting the law go into effect (so the Plaintiffs would encounter the displays) would be a “considerable hardship” upon those families. There’s no need to wait, he wrote, when the law was this blatantly illegal.

The bottom like is that this law is illegal for All The Reasons.

The judge has struck down HB 71, ordered state officials to notify every public school that the law has been declared illegal, and forced the Plaintiffs to pay a (mostly symbolic) $100 penalty.

What happens now?

This ruling will surely be appealed. But the judge’s decision will still be in effect while that process plays out, which means no Ten Commandments displays will be going up in Louisiana classrooms in the foreseeable future.

Louisiana officials had to know this wasn’t going to work, but they didn’t care. Their goal was always to get this legislation in front of their allies on the Supreme Court so that any remaining barriers protecting church/state separation could be struck down just like the Lemon Test was years ago.

But for now, church/state separation groups are celebrating the well-deserved victory:

“This ruling should serve as a reality check for Louisiana lawmakers who want to use public schools to convert children to their preferred brand of Christianity,” said Heather L. Weaver, Senior Staff Attorney for the ACLU’s Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief. “Public schools are not Sunday schools, and today’s decision ensures that our clients’ classrooms will remain spaces where all students, regardless of their faith, feel welcomed.”

“We are pleased that the First Amendment rights of students and families are protected by this vital court decision,” said Patrick Elliott, Legal Director of the Freedom From Religion Foundation.

“This ruling will ensure that Louisiana families – not politicians or public school officials – get to decide if, when and how their children engage with religion,” said Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. “It should send a strong message to Christian Nationalists across the country that they cannot impose their beliefs on our nation’s public school children. Not on our watch.”

“Religious freedom—the right to choose one’s faith without pressure—is essential to American democracy,” said Alanah Odoms, Executive Director of the ACLU of Louisiana. “Today’s ruling ensures that the schools our plaintiff’s children attend will stay focused on learning, without promoting a state-preferred version of Christianity.”

Jon Youngwood, Co-Chair of Simpson Thacher’s Litigation Department, added, “We are heartened by the District Court’s well-reasoned and detailed opinion, which rests upon the wisdom of the First Amendment to the Constitution and the protections it affords regarding the separation of church and state and the free exercise of religion.”

(This post will be updated as more information comes in.)

That this is even a conversation is sickening. Xtians need to stay in their lane and that's not the classroom, or any part of the government.

This is exactly what the christianists wanted - to get it into the appellate process. It will end up before these supremes of ours and they will pull more legal hocus pocus out of Alito's ass and eliminate the separation of church and state.