Hawai’i Supreme Court defends secularism in blistering rebuke of John Roberts' SCOTUS

Justice Todd Eddins blasted SCOTUS for twisting facts, favoring religion, and betraying the First Amendment

This newsletter is free and goes out to over 22,000 subscribers, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe or use my usual Patreon page!

The Hawai’i Supreme Court just delivered a stellar defense of church/state separation—and a rebuke to John Roberts’ conservative-majority U.S. Supreme Court—in a case that centers around a century-old land deal.

The question at the center of it is a simple one: Can the government require that a plot of land be used for religious purposes forever?

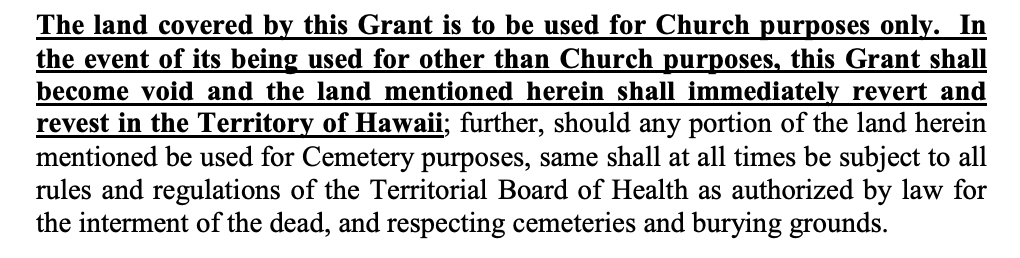

In 1922, the governor of the then-territory of Hawai’i sold a 3.99-acre plot of land to Heber J. Grant, a trustee for the Mormon Church, for $20. The contract for that deal, the “Land Patent,” included a restriction that said the land had to be used “for Church purposes only,” and that if they ever used it for anything else, the contract would become void and the land would once again be controlled by the state.

If you visited that land today, you’d never know it’s being used for religious purposes. It’s just vacant property. In 2000, that land was sold to a company called Hilo Bay Marina LLC, and in 2015, one of those parcels was transferred to “Keaukaha Ministry LLC” (which sounds like a religious group but isn’t). Both companies are owned by the same guy, David Owens.

Owens sued the state in 2022, arguing that his inability to develop those properties for anything other than religious usage was unconstitutional. He argued that the state couldn’t force him to abide by a religious restriction, and the fact that the restriction even existed violated both the Hawai’i and U.S. Constitutions. As his lawyers wrote in one brief, “SCOTUS has, in no uncertain terms, repeatedly confirmed that the Establishment Clause forbids both state and federal governments from aiding all religion to the exclusion of non-religion.”

The state responded by saying the original restriction was tradition. It was a “primitive form of zoning” and therefore still valid—even if it wouldn’t fly today. Plus, they said, there were plenty of examples of laws that had “religious roots,” like Blue Laws that keep retail stores closed on Sundays.

Owens team responded by saying even those laws had a secular purpose. You could make a non-religious case for why Sunday should be a day of rest for everyone. Those Blue Laws remained on the books in some places, they argued, not because of religious tradition, but because there was still an underlying secular purpose to them. But the land restriction at the center of this case? There was no secular justification for that at all.

Sadly, the judge agreed with the state and said the deed restriction was legal. He wrote that the original agreement was permissible because it was secular… in the sense that it allowed for “any religious organization to benefit from the property” rather than endorsing one faith over another. (See?! Just a run-of-the-mill zoning regulation!)

That decision was appealed and the case eventually landed in front of the Hawai’i Supreme Court, which issued its decision this month, unanimously striking down that religious-use restriction. They said the Deed Restriction “was not an early form of use-zoning” and that the Religion-or-Bust clause in the contract “violates Hawai‘i’s Establishment Clause in article I, section 4 of the Hawai‘i Constitution.”

Moreover, enforcement of the Deed Restriction is not a neutral act as between religion and non-religion. Rather, the Deed Restriction explicitly favors religion, requiring any owners of the Property to continue using it only for “Church purposes” or they will lose the Property. Hence, the State’s authority is directly utilized to support religion.

The justices also said that it’s ridiculous to consider “historical practices” here because, unlike the U.S. Constitution, Hawai’i’s Constitution came into existence far more recently and “there is nothing in the record to indicate that the framers of the Hawai‘i Constitution or the electorate considered such state actions as consistent with the Hawai‘i Establishment Clause adopted in 1959.”

All of that is great news and it means the property owner is no longer limited by religion when it comes to how he can develop his land.

But the real reason we’re talking about this story is because one of the justices, Todd Eddins, wrote a 40-page concurrence that Slate described as the “Most Withering Indictment of the Supreme Court Ever By a Sitting Judge.” In essence, Eddins denounced what the Roberts Court has said about religion over the years as part of an effort to strengthen church/state separation.

There are so many delicious passages in this concurrence but let me highlight just a few of them here.

Eddins agrees with the majority opinion but he says he wanted to write separately because he believes the state’s Establishment Clause “has a pluralistic purpose and secular spirit grander than the majority suggests.”

As jurists have long known, and as the people of Hawaiʻi who ratified our state constitution over the years understood, the promise of religious pluralism and secular government depends on a durable wall separating church and state. Without it, religion, government, and civil society suffer.

Eddins also says Hawai’i shouldn’t rely on federal law to inform how it interprets its own Establishment Clause. Hawai’i’s dedication to church/state separation, he brags, is much stronger.

If the Supreme Court decides a case based on mission, text trickery, originalism, or imagination, then that case may have little value to a state that prefers a more principled way, or an interpretive approach that does not force “contemporary society to pledge allegiance to the founding era’s culture, realities, laws, and understanding of the Constitution.”

…

The Roberts Court casually dismisses the lessons of American and world history, the warnings of prominent early Americans, and the judiciary’s storied legal minds. Bad things happen unless government and religion are completely separated.

The Court ditches neutrality and boosts accommodation over the wall. It flirts with the true harms the framers foresaw—coercion, exclusion, and civil strife. It invites state involvement with religion. And it exposes minority faiths and nonbelievers to majoritarian impulses.

Eddins went on to describe major church/state rulings from SCOTUS and how they created holes in the Wall of Separation to the point where “Now the government must equally treat secular and religious entities in public funding matters. Even when taxpayer money directly supports religious indoctrination.”

He concludes that section:

Taxpayer funds now flow to religious institutions. So, the government collects money from nonbelievers (under the threat of jail), and uses some of it to support religion. And since not all religions will receive public funds, the government forces minority faiths to support other faiths, or else.

The Court twists text, history, purpose, precedent, and public meaning to offend the First Amendment’s character-of-government structure and the Constitution’s separate sovereignty structure.

…

Today’s Court often rules not because the Constitution says so. But because partisan preferences and personal values say so.

Eddins goes for the jugular when describing the case of Joe Kennedy, the former high school football coach who claimed he had a religious right to perform public prayers at midfield immediately after games. SCOTUS sided with him, though the dissenting judges pointed out that they purposely lied about the “facts” of the case in order to justify their decision.

History is prone to misuse. The current Court shrinks, alters, and discards historical facts that don’t fit… It “handpicks history to make its own rules,” missing the broader context of a constitutional provision’s original and contemporary purposes.

…

Pretend law based on pretend facts and unsound methods has no place in Hawaiʻi law.

Finally, Eddins argues that the case in front of him is simple. It’s a “classic violation” of his state’s Establishment Clause.

For the reasons stated in the well-done majority opinion, a deed restriction imposed by the State that requires a landowner to use the land for “church purposes only,” or else it reverts to the State, constitutes state action that advances religion.

The State’s purpose in retaining a reversionary interest is not secular. It’s religious. The government does not just accommodate religious practice as a condition of property tenure, it forces faith-based use of the land. It conditions ownership and land use on the advancement of religious activity. The State compels religious use and excludes all secular purposes. It favors religion over nonreligion.

He saves his final words for Roberts himself:

Back then in the big games, the Roberts Court called balls and strikes based on the pitcher and hitter. Bad enough for the integrity of our judicial system—national and subnational. But now pitches that bounce to the plate or sail over the catcher’s head are strikes. Just because the ump says so.

Pretend law is not law.

State constitutionalism makes it easy to consider Roberts Court jurisprudence white noise.

As Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern said, “Justice Eddins didn’t leave anything on the field. He’s saying what nobody else, at least in the judiciary, seems able to say about the Supreme Court right now.”

This case, then, is ultimately not just about one parcel of land in Hawai’i. It’s about the integrity of our secular democracy. Justice Eddins’ scorching indictment of the Roberts Court underscores how far SCOTUS has drifted from the founding principle that government must remain neutral on matters of faith. By shredding the wall between church and state, the Supreme Court has betrayed its duty, leaving minority religions and non-believers vulnerable to coercion, exclusion, and forced subsidization of beliefs they don’t share. Thankfully, Hawai’i’s justices remind us that constitutional law doesn’t need to be twisted to achieve a desired result. Sometimes the answer is just straightforward and obvious—and secular.

It’s important to see a justice call out the Roberts Court for its religious favoritism, for bending the facts, for rewriting history, for cloaking their ideology in legalese to benefit conservative religious zealots, and for its judicial malpractice.

Hawai’i’s ruling calls for a renewed commitment to pluralism and secular governance. The contrast between the state court and the federal one couldn’t be more stark: While the U.S. Supreme Court erodes the foundation of church/state separation, Hawai’i shows us what it looks like when a court chooses principle over politics.

𝑇ℎ𝑒 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑝𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑑 𝑏𝑦 𝑠𝑎𝑦𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑜𝑟𝑖𝑔𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑤𝑎𝑠 𝒕𝒓𝒂𝒅𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏.

And we all know what tradition is: Peer pressure from DEAD PEOPLE. It's also the dodge that religion uses to insert itself into secularity, whether welcome or not, and in this case, clearly NOT. Justice Eddins clearly wasn't having any, and I thank and applaud him for his thorough and unforgiving statement on this issue.

It's way past time that SOMEONE stood up to the Roberts court.

Wasn't it Jesus-loving sugar warriors that came into Hawai'i and took it over? Look what happened to the native population and its land.

Christianity destroys everything it touches. Especially native cultures (as indigenous people of this country can attest).