Quebec's proposed public prayer ban is a blunt attack on religious freedom

Under the guise of “secularism,” the ruling Coalition Avenir Québec government is turning intolerance into policy

This newsletter is free and goes out to over 22,000 subscribers, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe or use my usual Patreon page!

The government of Quebec is on the verge of introducing a bill to ban public prayer, and they’re using Islamophobia to convince citizens it’s a wise move. The idea that public displays of religion might be outlawed has united several religious groups as well as civil rights and church/state activists who say this would be an obvious case of religious oppression, not to mention a violation of human rights that are supposed to be protected under Canadian law.

Quebec has been pushing mandatory public secularism for some time now. In 2019, they passed Bill 21, which said Quebec was a secular state, thereby banning religious symbols worn by certain government employees, including police officers, government lawyers, and teachers. It was (and continues to be) widely seen as an attack on religious minorities, like Muslims and Sikhs who can’t just not wear their hijabs or turbans the same way a Christian employee can tuck away a cross necklace. Yet while a majority of Canadians oppose the law, a 2019 poll found that 64% of people who live in Quebec support it.

More recently, Quebec’s government commissioned a report on the state of secularism in the province. The report was supposed to “document the phenomenon of infiltration of religious influences” and offer recommendations on how to strengthen Bill 21. It came on the heels of some well-known conflicts between religious groups and the Quebec government.

Last year in Montreal, for example, Muslims requested and received a permit to hold a morning prayer to mark Eid al-Adha. The mayor defended the permit by saying Christians were allowed to hold a public event in a local park and “If we allow an outdoor mass for one religion, we must also allow it for another religion.” (A sensible take!) But even that mayor then added: “It's not something we want to see more of. It's really very limited.”

But the real impetus is a sustained series of protests to raise awareness of the Israeli government’s genocide in Gaza. For the past several months, a group called Montreal4Palestine has been organizing those peaceful rallies outside Montreal’s Notre-Dame Basilica—and they’ve included Islamic prayers. (Counter-protesters have also been on the scene since the summer.) A spokesperson for the church has defended the gatherings, saying they are a “legitimate exercise of freedom of expression in an emblematic public space of Montreal.”

Is it free expression or is it a religious threat? That’s really been the heart of the conflict. Should the solution be preventing religious expression in public spaces entirely or just preventing gatherings that block traffic and violate noise ordinances? Many articles have noted that there are already local laws that go after groups disturbing the peace. They’re just not always enforced.

Anyway, the report about secularism was finally published last month (alas, only in French). Some of the recommendations are very rational, like ending the practice of telling parents in advance that their kids will learn about sex education in class. (By treating sex ed as any other school topic, it helps destigmatize the subject.) Others go in the other direction, like extending the ban on wearing religious symbols in “early childhood centers and subsidized daycares.”

What about when it comes to public displays of prayer?

The lawyers who wrote the report, Christiane Pelchat and Guillaume Rousseau, said that local municipalities should decide for themselves whether or not to take that step. But even then, they added all kinds of caveats, like what this one expert said to them (roughly translated):

A social science specialist told us that, in his opinion, a strong vision of secularism is legitimate and desirable for Quebec. However, he considers that such a vision is not incompatible with demonstrations by religious groups, provided that they are authorized by the authorities and that these religious groups are not favored over other, non-religious groups.

That was also a sensible take! Religious demonstrations and rallies aren’t contrary to public secularism. They’re a part of it. As long as everyone is treated equally, and everyone is respecting the law, have at it.

The report added that passing such a bill banning public prayers would create all kinds of other complications:

Would yoga be banned?

What about groups that consider watching the sunrise a spiritual event?

What about religious practices that are part of “open-air” weddings?

What about a St. Patrick’s Day parade—is that religious?

What about spiritual practices of Indigenous people that are meant to occur outdoors, like pipe smoking and powwows?

What about meditation?

Also, who the hell would enforce all this?

Those were all important rhetorical questions. That section of the report concluded with a formal recommendation (#36) saying that “municipalities must incorporate, in their secularism policies, a framework for collective religious events within their territory, in accordance with their regulations.” In other words, secularism is important, but it’s up to local communities to figure out how best to implement these policies.

It was a fairly moderate recommendation. But government officials are now using it in defense of something far more extreme.

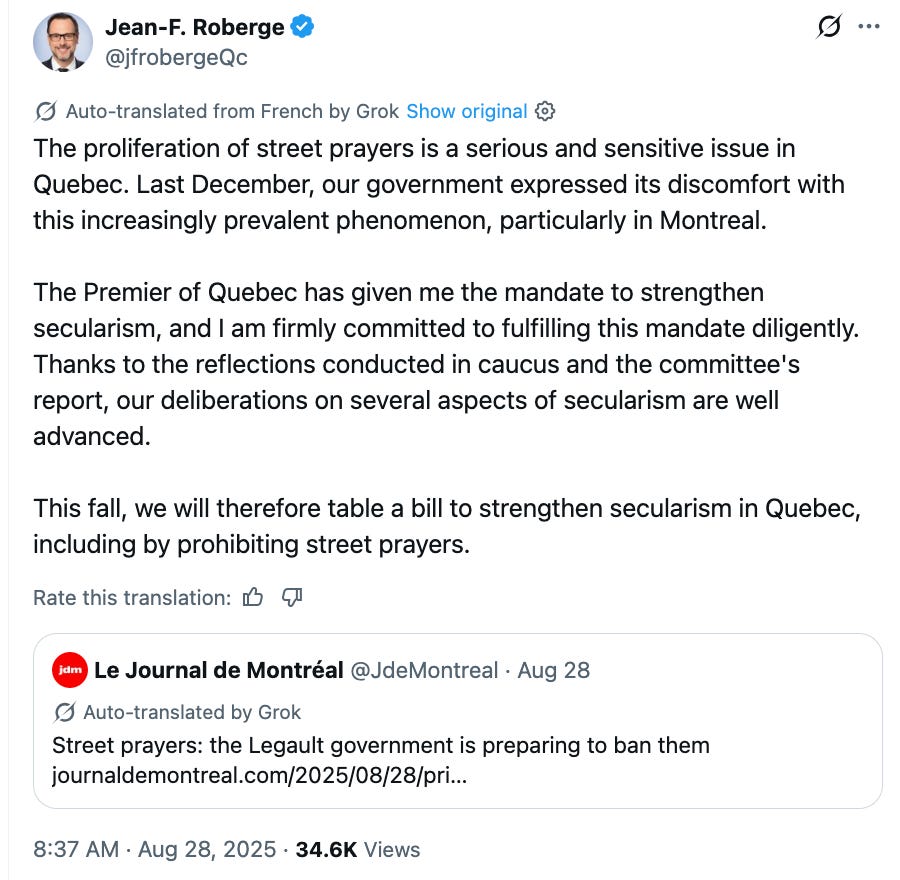

Consider Jean-François Roberge (pronounced roh-BAIRzh), the Minister Responsible for Laicity—basically, an enforcer of secularity. He said in a Tweet that the government needed to go even further to eradicate religion from public spaces by specifically eliminating public prayers and displays of faith. Forget leaving it to local communities; he wanted to do it across the entire province. And forget going after annoying protesters; this was far more sweeping.

The proliferation of street prayers is a serious and sensitive issue in Quebec. Last December, our government expressed its discomfort with this increasingly prevalent phenomenon, particularly in Montreal.

The Premier of Quebec has given me the mandate to strengthen secularism, and I am firmly committed to fulfilling this mandate diligently. Thanks to the reflections conducted in caucus and the committee's report, our deliberations on several aspects of secularism are well advanced.

This fall, we will therefore table a bill to strengthen secularism in Quebec, including by prohibiting street prayers.

(In Canada, tabling a bill means introducing it, not killing it.)

If you think that’s overly harsh, Roberge has the full support of Premier François Legault (pronounced luh-GOH), who called out Muslims in defense of his position:

"Seeing people praying in the streets, in public parks, is not something we want in Quebec," Legault said in December, saying he wanted to send a "very clear message to Islamists."

"When we want to pray, we go to a church, we go to a mosque, but not in public places. And yes, we will look at the means where we can act legally or otherwise."

It’s such a strange message even beyond unfairly conflating peaceful Muslims with “Islamists.” Prayer, to him, should only exist within the walls of a religious space. When you enter the public realm, that one aspect of your identity must be concealed. That’s especially true for one religious group in particular.

But as many Christians would say, their faith isn’t confined to the walls of a church. The idea that the government would punish people who are peacefully (even quietly!) praying in a public space is ludicrous.

To ban public prayer, columnist Toula Drimonis wrote, is like “using a bazooka to kill a fly,” adding:

Public prayers genuinely meant to raise awareness about the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians, including far too many children, shouldn’t be treated as an existential menace to Quebec’s secularism.

Of course it shouldn’t. Yet that’s exactly what defenders of the proposed bill are saying.

Mathieu Bock-Côté, a conservative commentator who is very influential among Legault and his allies, was very blunt about why this proposed law was necessary, using “Great Replacement Theory” rhetoric in the process:

We are talking about a conquering Islam, that is to say an Islam shaped by Islamism and carried by waves of migration transforming the demographic composition of our societies.

…

Why not also remember that while Quebec is a secular society and must push this secularism further, notably by banning ostentatious religious symbols in schools, it is also a historically Catholic society. Those who have a problem with this should ask themselves why they want to live there.

A street prayer in front of a church, or in the middle of a city center, is about turning the freedom of religion offered by liberal democracy against itself.

It is a symbolic aggression.

It is not forbidden to defend oneself.

Or—hear me out—protests that include prayer can just be a personal display of faith that affects no one else…

When I first saw the headlines about this story, I thought the government was trying to ban street preachers or unwanted religious solicitors who invade other people’s personal spaces in an effort to convert them. Or maybe they were going after proselytizers who were over-the-top public nuisances. But that’s not the case here at all.

What this government wants is the kind of religious oppression Christian Nationalists in the United States pretend to experience.

It’s been interesting over the past week watching the various reactions to the proposed legislation. Even though no one knows what the eventual bill will say, the idea itself has generated all kinds of backlash from a variety of groups:

The head of the National Council of Canadian Muslims says the ban is concerning.

“The idea that somehow prayer in the street is a new thing or a dangerous thing is absurd,” said CEO Stephen Brown.

…

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association said banning prayer in public spaces would infringe on freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association.

"Public spaces belong to everyone, regardless of their religious beliefs," the association wrote in a statement. "These spaces must be places where diversity of belief, culture and identity is both respected and protected."

…

“Street prayers are a manifestation of freedom of expression that has been exercised for so long by various communities, rights guaranteed by the Quebec and Canadian charters,” the statement [from the Canadian Muslim Forum] said. “A blanket ban would stigmatize communities, fuel exclusion and undermine Quebec’s social cohesion.”

…

Rabbi for Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom, Lisa Grushcow, said a ban on public prayer would be “a real loss,” and certain Jewish traditions require a body of water in nature, especially during the High Holidays starting next month. “I don’t think that someone’s discomfort, including the premier’s, should shape what policy is,” she said in a phone interview.

André Pratte, a journalist and former lawmaker himself, said it well: Public displays of religion aren’t real problems and this is nothing more than a new way to stoke fear of Muslims among voters who don’t know any better:

Let us be clear here: it is not prayers in public places that are disturbing; Catholics have been praying in public for decades and no one has ever protested, even though Quebecers have thrown religion in the trash. No, what is disturbing is Muslims who pray, in the same way that the ban on religious signs was really aimed only at the Muslim headscarf.

In Quebec, practicing Muslims cause discomfort; they worry; they disturb. In a population that is not familiar with these practices and that has rejected religion, this discomfort is understandable. But that is no reason to violate people's fundamental rights.

…

And all this to solve what problem? If there are prayer demonstrations that disrupt public order or traffic, the police forces already have all the powers to intervene. There is no need for a new legislative arsenal that will make a religious practice disappear from public space simply because many Quebecers are instinctively hostile to it.

This feels in many ways like a Bizarro World version of what’s happening in the United States. Christian Nationalists here have taken over the government and made it their mission to eradicate the persecution of Christians (which isn’t a real thing). One way they’ve done that is by spreading lies about Muslims, leading to things like a Muslim Ban, and calls for Muslims to be banned from holding office, and all kinds of religious smears against New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani. Similar smears have been aimed at Rep. Ilhan Omar.

In Quebec, officials are using the goal of a secular government to push the same baseless attacks on the same religious minority.

The British Columbia Humanist Association, which is obviously far from Quebec but which has fought its own church/state battles in the country, believes the government is going too far in the wrong direction. The BCHA’s executive director Ian Bushfield told me:

We're obviously troubled by these moves. Further, we worry that these threats to individual rights and freedoms may overshadow the important recommendations in the Pelchat-Rousseau report that would help dismantle the privileges that institutional religion continues to enjoy in Quebec and across Canada. Our quest for a more secular society should target those with power—governments and institutions—rather than the individual believer just trying to live their life.

There’s another element worth considering, too: The ruling party is heading into next year’s elections with awful approval numbers. They’ll do anything they can to rally their base, and conservatives have a nasty habit of using bigotry to do that. Here’s Pratte once again summarizing what others reports have also echoed:

Roberge’s announcement comes at a time when Legault’s party, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), has dropped to third place in the polls, a year away from the next provincial election. For months now, the caquistes have been looking for an issue that would help them rise from the dead. They may have found it by this new attack on Quebecers’ fundamental rights.

Give it time and Legault will probably claim Muslims are eating your pets.

It’s no wonder one Redditor joked, “How long am I allowed to close my eyes in public before I've committed a crime?” (One response? “Depends - what colour is your skin?”)

There are atheists, however, who are fully in support of this proposed law. Michel Virard, the president of the Association humaniste du Québec, told me he saw the protests as a “relentless, subtle war of provocations” and that’s why he backs the proposed prayer ban:

We are now facing systematic provocations by Muslim activists, some of whom will deliberately call for violent actions against Jewish persons and properties. Letting them literally occupy the public sidewalks for their own religious proselytism is not something we are going to accept.

While calls for violence against Jewish people can and should be condemned, the proposed law would apply to everyone who prays in public, not just people using their faith to justify extremism. It feels very much like deliberate overkill. (I raised that issue with Virard, but he didn’t respond.)

Needless to say, I don’t agree with his take at all. Interestingly enough, the BCHA and Virard’s group are on opposite sides of Bill 21 in a case that will soon be heard by the Supreme Court of Canada. Which is to say the atheists are not aligned on this particular issue.

The bottom line is that what’s happening in Quebec is not secularism. It’s a perversion of it.

When we talk about the importance of church/state separation, it means everyone is protected under the law and no single belief system promoted by the government dominates the public square. It doesn’t mean that all faith must be driven out of it.

This proposed bill isn’t about neutrality. It’s about control. The Coalition Avenir Québec wants to wield state power to single out Muslims under the guise of order and “discomfort.” It takes the legitimate principle of secularism and weaponizes it, using it as a bludgeon against a vulnerable minority, while pretending the oppression is fairness.

Make no mistake: if this bill moves forward, it will not be a victory for secular values. It will be a betrayal of them. Certain non-Muslim groups will be allowed to celebrate their faith-based traditions in public while others will be criminalized for doing the same. The bill will embolden xenophobes and reward politicians who gamble with human rights to win votes. And it will send an unmistakable message—not only to Muslims, but to every religious and non-religious minority in Quebec—that your freedom is conditional, your belonging is negotiable, and your dignity is expendable (at least when the polls demand it).

The Globe and Mail columnist Robyn Urback put it well:

A law banning public prayer is an unconstitutional, unnecessary distraction that some will support because they don’t like to see Muslims praying outside a church. But government is not justified in banning behaviours that simply make people uncomfortable, and especially not when we already have rules against behaviours that actually impede the flow of others. We don’t need to create new laws; we just need to enforce the old ones.

This bill won’t solve any problems. It’ll just create new ones, no matter what the actual text says when it’s finally introduced.

I don't care if they pray to their imaginary friend as long as they don't inflict their misery on others.

Secularism should only apply to the government and how it operates its programs, institutions, and laws. It is about neutrality of the government, it should not be a mandate for the citizens. The way the USA constitution works is that it provides restrictions and rules about how the government works and what it can do, restricting the government from interfering in the rights of the citizens. What it doesn’t do is tell citizens how to live. The laws congress and the states come up with are the rules for citizens and these rules must comply with the constitution. I do not know about Canada’s constitution, but I imagine that it is similar. If there is a protection of religious freedom, then this law is unconstitutional. But to restrict prayer by the citizens in public, does nothing but oppress. It will lead, rightfully, to rebellion by the people.

It is never a good idea to restrict things to this extent.