Ignoring racism won’t fix racism: A response to Robyn Blumner's misguided essay

Arguing for a color-blind society, the CEO of the Center for Inquiry ignored the realities of racism

This newsletter is free, but it’s only able to sustain itself due to the support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. Would you please consider becoming one of those supporters? You can use the button below to subscribe to Substack or use my usual Patreon page!

In the August/September 2024 issue of Free Inquiry, Robyn Blumner, the CEO of the Center for Inquiry (which publishes the magazine), wrote an editorial called “Secular Humanism and the Color-Blind Society” in which she argues that Humanists can and should look beyond race in order to create a “color-blind society.” The piece is behind a paywall.

It contains so many problems, however, that I asked Bakari Chavanu, a co-founder of Black Humanists and Non-Believers of Sacramento, to write a response to it. His essay is below.

As a Black atheist, humanist, and leftist, I was deeply appalled and offended to read Robyn Blumner's piece. After years of grappling with racial discrimination and striving to comprehend how racism operates within white supremacy, I had thought that self-proclaimed humanists would grasp the fallacy of a "color-blind society."

The very concept is misguided. It seeks to erase the unique experiences and struggles of Black and other minority people under the guise of racial equality. It's also a concept that glosses over the systemic racism that is deeply entrenched in our society.

In her editorial, Blumner claims that the “identitarian Left” perpetuates racism and makes "skin color an essential qualification or disqualification for life's rewards." She doesn’t bother providing examples of this or citing any sources, but she insists it wasn’t always like this:

Color blindness used to be the aspiration of nearly everyone who supported the civil rights movement. It stood in stark contrast to the Black Panther and Nation of Islam approach to Black empowerment that was more segregationist, Black supremacist, and anti-White.

Interestingly, Blumner doesn’t acknowledge the historical context of these organizations and movements, which emerged as a response to legal racial segregation, white violence, lynching, police brutality, and systemic disenfranchisement of Black people.

For what it’s worth, the Ten-Point Program of the Black Panther Party does not espouse Black supremacy. While the Nation of Islam has preached the so-called inherent superiority of Black people over white people, it has never created policies and practices that marginalize white people. To put it another way, there is both historical and contemporary context for Black resistance to white racism and domination. You cannot transcend race when you don't acknowledge the historical (racist) harm to, violence against, and marginalization of Black people.

The two groups she mentions emphasize Black empowerment, cultural pride, and self-defense against systemic racism and violence against Black people. Those goals have never marginalized white people or brought about Black supremacy anywhere in the country, and those are not the goals for today’s Black left either. Reverse racism isn’t the bogeyman she makes it out to be. Yet Blumner, speaking as a humanist, argues that the biggest obstacles to a color-blind society and racial harmony are supposedly Black supremacy and neo-racism, not the history and culture of white supremacy and racialized capitalism.

The goals of the civil rights movement aimed to end racial segregation and discrimination while creating opportunities for access to education, housing, employment, political empowerment, and wealth accumulation. Integration only benefits marginalized groups if they consistently have access to the opportunities and resources that might empower them. And yes, that includes reparations for historical harm, theft of labor, and loss of generational wealth.

Yet Blumner writes that the racism of the past is simply not that big of a deal because most of us know better today:

Most White people in the United States these days are not racists. I say "these days," in 2024. You can point backward to a different reality. There are still racists of course, but in general we have excised that demon as we have sloughed off other old prejudices, such as that women shouldn't work outside the home or that LGBTQ people shouldn't legally marry each other. We have made stunning progress shifting all those attitudes within my lifetime—a cause for unbridled celebration especially among humanists, many of whom were at the forefront of these civil rights struggles.

She’s ignoring what’s happening right in front of our eyes. Even if most white people are not racist, racism permeates the actions of many of the most powerful people in the country.

How can anyone pretend that the current Republican presidential candidate and Republican policymakers nationwide are “color-blind”? They wage campaigns using “Critical Race Theory” and "wokeness" as dog whistles against Black and other marginalized groups, deeming certain ones as an impediment to their supposed values.

For all the progress that certain groups, including women and the LGBTQ community, have made when it comes to civil rights, the obstacles have almost always been created by the same kind of people who perpetuate racism today. That goes well beyond individual prejudice. It’s systemic. And that’s why addressing the problem requires a comprehensive understanding and dismantling of the structure upholding these disparities.

Blumner also targets Ibram X. Kendi, a prominent advocate of antiracist justice:

If you are not racially discriminatory toward White people, according to Ibram X. Kendi, a godparent of the identitarian Left, you are racist. "The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination,” Kendi wrote, in words that would be softened in a future edition after they became the subject of criticism. "The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.” In other words, two wrongs do make a right. As practiced, that meant curriculums that favor works by Black people over White people are one way to achieve that goal; hiring quotas are another. Yet preferring one race over another, Kendi's explicit playbook, is the very definition of racism. Reverse racism is still racism, as [Dr. Martin Luther] King [Jr.] well understood and called out.

Kendi's assertion, found in his book How to Raise an Antiracist, that the "only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination" is rooted in the need to address systemic inequalities through proactive measures. Because of systemic discrimination, marginalized groups have faced historical disadvantages. If racism magically ended today, it wouldn’t make up for those vast, historic discrepancies. Antiracist discrimination, as Kendi describes it, involves implementing policies that actively favor marginalized groups with the aim to counterbalance past and present injustices by making structural changes and rectifying imbalances.

Why do what Blumner writes off as “reverse racism”? Because it’s a necessary step toward dismantling racial and economic injustice.

We cannot achieve equity while systemic barriers like unequal education, discriminatory housing, high incarceration rates, and class oppression persist. Without addressing these issues head-on and intentionally, a "color-blind society" remains superficial and unattainable.

One argument against that approach to equity is that some people have overcome those obstacles, and therefore, others should be able to do the same. In fact, Blumner raises the conservative banner that racism really isn’t an issue anymore because there are many Black people in positions of power:

There are still inequalities, and we should continue to work on those. How to do that best and most effectively, however, is not to double-down on the enfeebling notion that every Black person is a victim of a systemically racist society and under those circumstances their lot is to be oppressed and downtrodden. Especially because reality says differently. We have a current Black vice president, secretary of defense, ambassador to the United Nations, chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, and two U.S. Supreme Court justices. As these examples and thousands like them demonstrate, in today's America people can largely succeed irrespective of their race.

We may have another Black president very soon, too, but none of that overrides the existence of systemic racism. Pointing to a few successful people doesn’t mean others with a similar racial background have no obstacles in their path.

Also, Clarence Thomas?! A Black Supreme Court justice who perpetuates white supremacy through his rulings while also pulling away the bootstraps that may help other minorities isn’t something to celebrate. (Similarly, the ascendance of Amy Coney Barrett wasn’t a win for feminists, given her positions on abortion rights and bodily autonomy.)

Despite the gains many Black people have made and are making in this country, the unemployment rate for Black people is consistently higher than for white Americans. A study from the RAND Corporation reveals that, in 2021, “an estimated 64% of unemployed men have been arrested and approximately 46% of unemployed men have been convicted of a crime by age 35.” Housing discrimination remains an issue as well, with studies showing significant Black-White response gaps from landlords, blocking Black families out of neighborhoods with high-quality schools. Even in education, disparities exist. While 88% of Black or African-American adults have a high school diploma, this is still lower than the 90% national average, another study reported. As of 2022, the median wealth of Black families was $44,890 compared to $285,000 for white families. These disparities reflect the ongoing impact of structural racism in wealth accumulation. The fact is that far too many Black people are denied access to resources and opportunities afforded to white people.

Also, consider the historic practice of redlining, where banks and insurers historically denied loans and insurance to residents in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The Joint Center for Housing reports that this practice has led to long-term economic disadvantages for these communities, limiting access to home ownership and wealth accumulation. Even today, the effects linger, with Black families often facing higher interest rates and fewer opportunities for property investment compared to their white counterparts.

None of this will change unless we take proactive steps to fix it.

Additionally, the criminal justice system disproportionately impacts Black Americans, leading to higher rates of incarceration and more barriers to reentry. One Pew Research Center survey reported that a staggering 79% of Black adults had personally experienced discrimination because of their race or ethnicity. A different study found that over 50% of Black Americans experienced discrimination in police encounters specifically.

Racist conservative ideology seeks to use the focus on a "color-blind society" to cloak racial disparities, making it harder to expose racial injustices and forms of discrimination. Aspirations of a society where the color of someone’s skin is ignored do not get us to the goals of economic justice and dismantling racism. True equity requires systemic change, not just individual achievements.

Affirmative action is one of the most potent tools to fix that problem, but Blumner assures us that Black people don’t really want it:

Such stark reverse discrimination of the Kendi variety is certain to stoke racial and ethnic resentments. And even Black Americans reject that kind of intervention. A Gallup poll from Fall 2023 found that nearly seven in ten Americans thought the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling curtailing affirmative action in college admissions was "mostly a good thing,” including 52 percent of Black Americans. Why? Because to people of goodwill, admitting people to elite universities based largely on one's race puts an unfortunate asterisk on the academic careers of those admitted through an unfair process. It harms the very people it purports to help.

Blumner didn’t mention that, among Black adults (the people who may have benefitted from those policies in the past and who may have a stronger understanding of the gains of the Civil Rights movement), only 33% supported the Supreme Court decision. It also depends on how the question is asked. A Pew Research Center survey from 2023 that didn’t revolve around the Supreme Court’s decision found that, while 47% of Black Americans supported the use of race and ethnicity in the admissions process for selective colleges, only 29% of them opposed it. (Another 24% were not sure.)

It’s also worth mentioning that banning “race/ethnicity in admission decisions,” as the Gallup survey asked, might sound good to people who aren’t as well-versed in the consequences of that decision. (Similarly, returning abortion rights to the states might sound good to many Americans, but people who understand the impact are overwhelmingly opposed to it.)

That Gallup poll also ignores the fact that race wasn't the main factor for admitting Black students into elite universities under affirmative action. They did not just get admitted because they were Black; those colleges considered various factors beyond test scores, including race, which helped level the playing field. The idea that it somehow diminishes minority students' achievements misses the point. It overlooks the complex nature of merit and the systemic hurdles these policies aim to tackle. High-achieving but disadvantaged Black students graduate from less-resourced schools but nevertheless have the academic skills and commitment to excel in elite universities. In such cases, universities take a holistic approach to the admissions processes that consider factors beyond standardized test scores. It’s a win-win because school diversity enriches everyone's learning and better prepares all students for the future.

This is why affirmative action aligns with Kendi's perspective, which is that it can deliberately create opportunities for historically marginalized groups to counteract systemic disadvantages. However, this responsibility shouldn't fall solely on elite universities, which have historically contributed to systemic racism and created barriers for Black and economically disadvantaged students. We should focus on adequately funding and resourcing historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to offer high-quality education to these communities, reducing the dependence on elite institutions. Even better, we should aim to provide affordable or free higher education for everyone, eliminating financial barriers altogether.

Later in her piece, Blumner cites a passage from Coleman Hughes’ book The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America to justify her belief that racism is no longer a huge problem:

One interesting poll Hughes cites is a 2013 Gallup survey asking Blacks in the United States the following question: "On the average, blacks have worse jobs, income, and housing than whites. Do you think this is mostly due to discrimination against blacks, or is it mostly due to something else?" Fully 60 percent of Blacks answered "something else" meaning a solid majority did not think racism was the primary cause of disparities in life outcomes, contrary to the identitarian Left's insistence.

That framing suggests only two explanations for this reality: (1) racism or (2) something else. However, "something else" can still involve racism! Just because people aren't overtly racist—like wearing white hoods or using racial slurs—doesn't mean the effects of systemic racism can be dismissed. Assuming that "something else" isn't racist implies it's an inherent issue, like suggesting Black people haven't taken personal responsibility or lack the work ethic and cultural values needed to succeed. These beliefs only serve to perpetuate systemic racism.

Also, from an anti-racist and anti-sexist perspective, there’s nothing wrong with identity-based politics. Everything can be identity-based, depending on who it affects. Hell, economic policies that benefit the wealthy are just identity politics for rich people. So what’s wrong with promoting policies centered around making society better for people who have faced obstacles due specifically to their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, or nationality?

Dismantling social, economic, and political injustice requires a consistent critique of how racialized capitalism and sexism can marginalize people because of their racial, gender, and class identities.

Blumner doesn’t want to do that work. Instead, she argues:

You don’t bring a diversity of people together by dividing them by skin color or making skin color an essential qualification for disqualification for life’s rewards. You bring them together by making racial distinctions as irrelevant as humanly possible — which is what color blindness means. It does not mean we are blind to skin color. It means our best to treat people equally without regard to it.

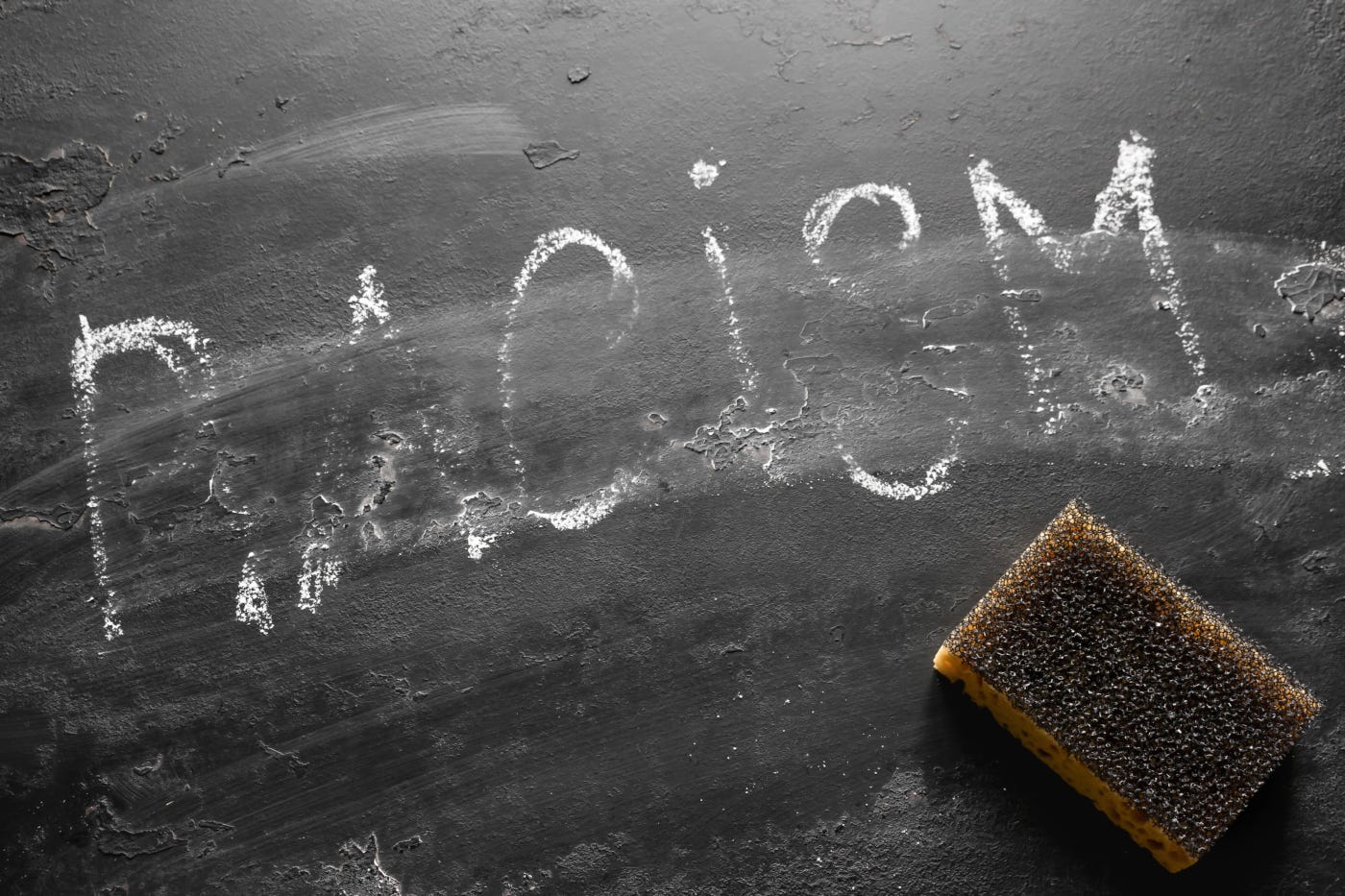

Ignoring racism won’t fix racism.

We don’t need to adopt color-blindness. We must acknowledge intersectionality, which values diverse experiences and identities and fosters empathy and understanding. By respecting these differences, we can build a fair society where everyone is valued without erasing what makes us unique.

Secular humanism should celebrate diversity and advocate for social, economic, and political justice. Instead of ignoring systemic disparities and injustices, it should highlight them and work to eliminate them. Our goal should be a society that values and respects our differences, acknowledges past and present injustices, and actively pursues equality and justice for all.

Humanism should amplify voices that have been historically marginalized and silenced–voices that challenge systems of oppression that persist today. As humanists, we advocate for social justice and equality for all. This is the humanism I believe in and promote.

Bakari Chavanu is a co-founder of Black Humanists and Non-Believers of Sacramento. He’s also a web designer and media content producer.

The 11 o'clock news last night here in Cleveland had a story of a black man in Canton, Ohio (south of here) who was killed while being arrested in much the same fashion as George Floyd was. Knee on the back or neck, "I can't breathe," repeated but not heeded, only this time the man's death was ruled a homicide by the coroner. I suppose that's something.

Being colorblind is fine ... IF (and that's an "if" the size of Lake Erie!) there is genuine equity and justice for EVERYONE. The stupid, blunt fact is that for people of color, we're nowhere near that, and there are too many law enforcement officers out there who are far more interested in protecting and serving themselves than they are in genuinely serving the citizens of their community. I've heard so many stories of this kind that the names start to blur together, but the color of their skin remains a constant reminder of a problem that jerks like Blumner want to ignore or sweep under the rug for whatever reason.

I've lived in a mixed neighborhood for the last 15 years, and I like it. I have great neighbors on either side of me and I'm glad of it ... and I wonder and sometimes worry if one of them might find themselves subject to such treatment. I don't think I could keep quiet if it did.

Racism, like religion, is learned behavior. Like religion, many children are indoctrinated with racial bigotry before they reach the age of reason. An unfortunate number of people go through life never being able to get past what they were force fed as children. I don't know what the solution is. I wish I did. One bright spot I'm seeing is the younger generation appears to be a lot more tolerant than their parents. I hope this trend continues.